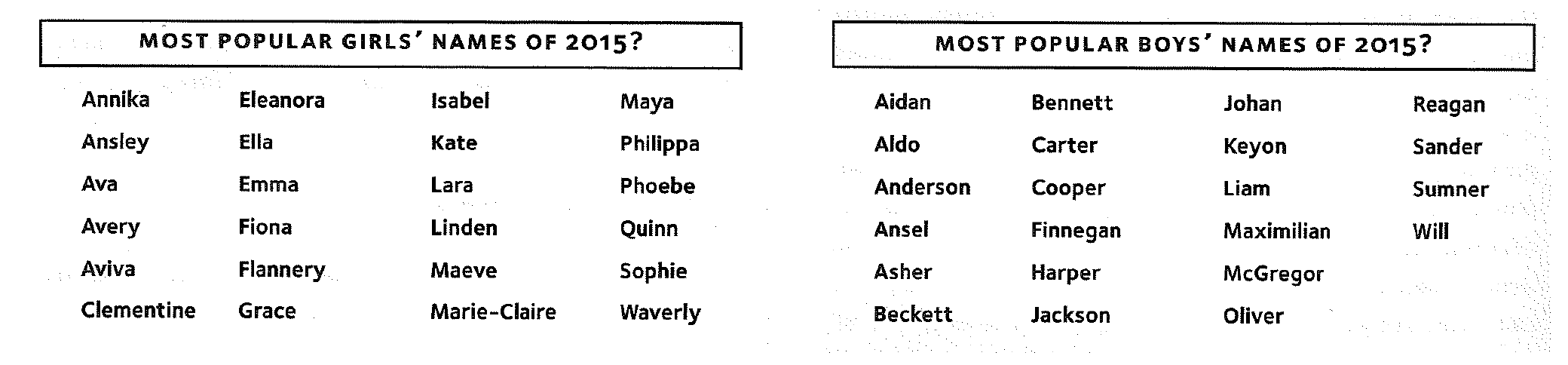

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # What to learn from baby names ] .subtitle[ ## A Social Data Science Story ] .author[ ### David Garcia <br><br> <em>ETH Zurich</em> ] .date[ ### Social Data Science ] --- layout: true <div class="my-footer"><span>David Garcia - Social Data Science - ETH Zurich</span></div> --- # US SSA baby name data <img src="BabyNameTrends_Slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-1-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Baby name trend examples <img src="BabyNameTrends_Slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-2-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # The QWERTY effect in baby names The QWERTY effect is a hypothesis in Psychology that postulates that words that are written with more right-hand letters of the keyboard are, on average, more positive than words that are written with more left-hand letters of the keyboard. The fraction of right-hand letters in US baby names has been increasing: <img src="BabyNameTrends_Slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-3-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Wacky baby name research <img src="BabyNameTrends_Slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> A parody paper titled ["We are entering an unprecedented age in baby name flux"](https://instsci.org/h7.html) reported; "baby name diversity also seems to have risen with the increasing annual temperature of the US (i.e., climate change)". --- # The limits of baby name predictability Baby names are a popular example to illustrate scientific topics. The book [Freakonomics](https://freakonomics.com/books/) explains the imitation part of the Simmel effect and explains how people imitate their richer neighbors when naming their babies. The book goes as far as making a prediction of what will be the top US baby names in 2015, based on a data analysis exercise that is never explained in detail in the article. Here is the prediction:  --- ### Top 10 names in 2015 and 2004 |topFemale2015 |topFemale2004 |topMale2015 |topMale2004 | |:-------------|:-------------|:-----------|:-----------| |Abigail |Abigail |Alexander |Andrew | |Ava |Ashley |Benjamin |Christopher | |Charlotte |Elizabeth |Ethan |Daniel | |Emily |Emily |Jacob |Ethan | |Emma |Emma |James |Jacob | |Harper |Hannah |Liam |Joseph | |Isabella |Isabella |Mason |Joshua | |Mia |Madison |Michael |Matthew | |Olivia |Olivia |Noah |Michael | |Sophia |Samantha |William |William | --- ## Predicting is hard There is not much overlap between the prediction and the results for 2015. Just using the 2004 list, you would have made a better prediction. What you see is that predicting which names in particular will be the most popular is a very difficult task. The Simmel effect describes forces that create observable patterns, but that does not mean that the model is predictive to tell us which of all names will become popular ten years from now, even if we had data of the social status of parents. This is the difference between explanatory and predictive power of a model. A model can explain phenomena without being useful to make predictions, as in this case, but can also be predictive without giving explanations, like in the case of deep learning or other black-box approaches. > **Take home message:** understanding does not imply predictive power